[ad_1]

Parks for Revenue: Promoting Nature within the Metropolis

Kevin Loughran | Columbia College Press | $30

In September, New York mayor Eric Adams introduced $35 million in funding for the design and development of the primary part of QueensWay, a linear park proposed to stretch from Rego Park to Ozone Park. The primary stage of the undertaking, known as Queensway Metropolitan Hub and designed by WXY and DLANDstudio, will start to remodel the long-abandoned Rockaway Seaside Department line right into a 5-acre open house to be managed by the NYC Parks Division and the NYC Financial Growth Company. Along with seemingly foreclosing on QueensLink, a rival proposal to reuse the railway for a brand new subway connection, the QueensWay’s first stage—a comparatively small path bisecting the 534-acre Forest Park—raises questions on its necessity.

The obvious precedent is Manhattan’s Excessive Line, however, at 13 years outdated, the now-teenage wunderpark has misplaced a little bit of its preliminary veneer of novelty. In 2009, when it opened, important new park initiatives had been unusual, not to mention parks long-established out of an outmoded elevated prepare monitor. However now the typology feels acquainted, a lot in order that untouched artifacts of main cities’ industrial ages—“diamonds within the tough,” or gems even—have grow to be scarce. Invariably, of their place, you’ll discover the identical obsessively programmed pathways, the acquainted overpriced concessions, and, in fact, a swath of recent speculative actual property doggedly lining the perimeter. In his current guide Parks for Revenue, Temple College professor of sociology Kevin Loughran asks: What was being bought with the postindustrial park?

To construct his thesis that such restoration initiatives helped usher in a brand new species of privately owned/developed parks, which in flip fueled intense speculative actual property growth close by, Loughran undertakes a comparative historical past of the Excessive Line and two related parks that had been developed in its wake: the Bloomingdale Path/606 in Chicago and Buffalo Bayou Park in Houston.

Loughran’s story begins in Chelsea with the Associates of the Excessive Line, which was based as a grassroots effort by well-connected residents to protect the deserted prepare line within the face of slated demolition on the previously industrial West Facet of Manhattan and follows the undertaking’s development right into a signature accomplishment of the Bloomberg administration. Following the Excessive Line’s success, Loughran’s story strikes to Chicago to recount how the Associates of the Bloomingdale Path’s grassroots imaginative and prescient of a extra inclusive intercommunity park was absorbed by the Belief for Public Land and the Rahm Emanuel administration and, lastly, to Houston to position the top-down Buffalo Bayou Park inside a bigger downtown revitalization plan within the face of city decentralization. Conveniently, the often-meandering construction of the guide follows Loughran’s tutorial appointments.

Nevertheless, regardless of some clear variations specified by the consecutive summaries of those parks’ growth, all three got here at a time of renewed enthusiasm for cities after a interval of perceived decline. For Bloomberg, initiatives just like the Excessive Line—designed by James Nook Subject Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro with Piet Oudolf—had been key to attractive the “artistic class” to maneuver again to New York, following a long time of white flight. There had already been a shift towards privatizing parks because the Eighties, with builders constructing public plazas in trade for top bonuses, and high-profile non-public park companies such because the Central Park Conservancy emerged to fill the funding hole for some inexperienced areas as town’s Parks Division confronted disinvestment. Whereas the blueprint for personal growth and administration was already set, to seize a spirit of authenticity, the postindustrial park wanted a brand new aesthetic to match these buzzy ambitions.

In distinction with the picturesque of Olmsted’s once-dominant fashion of panorama structure, Loughran mints the time period imbricated areas to explain the intermingling of business decay with managed nature. As an alternative of evoking an idealized countryside with winding paths, diverse elevation, and serene water options like these in South Park (now Jackson Park, Washington Park, and Halfway Plaisance) in Chicago, or NYC’s Central Park, imbricated areas romanticize “industrial landscapes, and, relatively than rebuking urbanization, have a good time (a selected perspective on) town’s visible qualities,” based on Loughran. Manicured lawns are changed with concrete paths, fastidiously interspersed with grass poking by the cracks.

Embodying the aspirations of the post-urban-decline development machine, this aesthetic valorized the underdeveloped. Loughran argues that these postindustrial parks “deliver collectively nostalgias for hazard, intercourse, medicine” and customarily “generally tend to fetishize and sexualize the joy and/or worry that gentrifiers discover in ‘discovering’ furtive locations.” With the assistance of engineers and panorama architects, some expanses which have been considerably ugly or unsavory to an incoming greater revenue bracket have been made “protected” and fed again to guests in an simply consumable package deal.

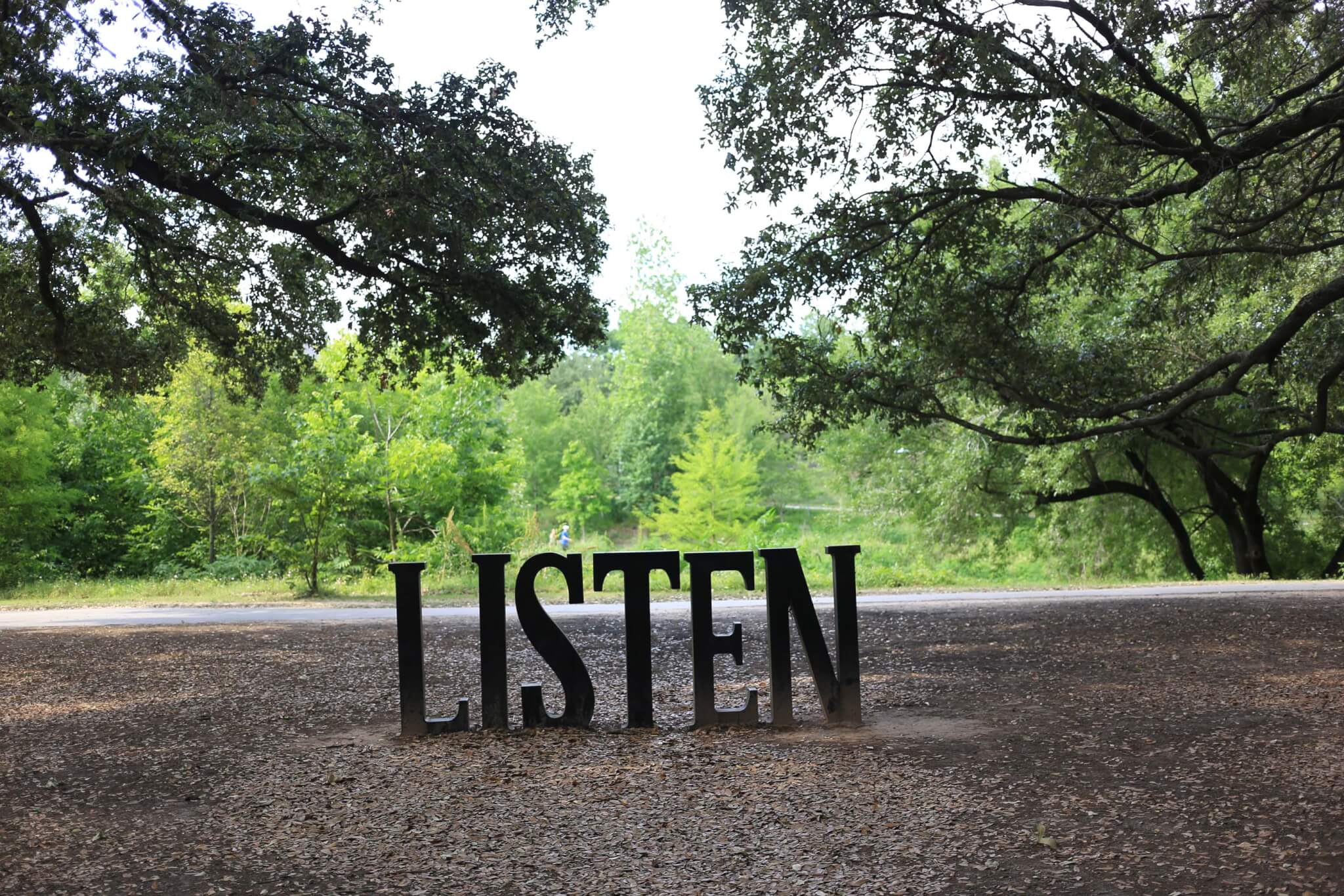

Loughran argues that this fashion naturalizes these parks throughout the up to date metropolis. As an alternative of getting the identical influence because the totalizing plans for parks up to now, postindustrial parks seem extra pleasant and inevitable. Buffalo Bayou Park, designed by SWA and Web page, is fastidiously populated with the “form of nature which may have existed, had an outdated Bayou not been channelized and planted with the ‘incorrect’ grasses and bushes, or if elevated railroads had been left effectively sufficient alone.” What outcomes from these constructions of environmental authenticity are “ecologically applicable areas with unimpeachable cultural authority,” not only a “capitalist development machine.”

Moreover, parks just like the 606—designed by a crew that included Ross Barney Architects, Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, and Arup—are examples of a “new and highly effective city ideology, which proposed that cities, as dense, communal, carbon-friendly areas, are humanity’s finest hope of surviving local weather change.” This constructed authenticity, coupled with the architectural language of adaptive reuse, generally is a potent image of local weather adaptation to which cities and companies can connect themselves.

It’s not simply the foliage that’s naturalized. The connective passages of this trio of parks use a brand new socially constructed idea of nature to Computer virus a brand new wave of growth into seeming inevitable: The programmed paths simply result in “consensual surveillance,” the “distinguished” concessions are overpriced and focused of their messaging, the non-public governance ensures aesthetic continuity, the large public subsidies lure actual property buyers to strike whereas the iron is sizzling, the residence buildings go up shortly, and the inevitable rising property values within the space quickly make it more durable for low-income residents to stay of their houses. At its finest, Parks for Revenue illuminates the disconnect between the best way these initiatives had been bought to the general public with the fun of thrilling new public areas and the gentrifying influence that they had on their surrounding areas.

Even in new parks that weren’t constructed out of adaptively reused infrastructure, like New York Metropolis’s Little Island, a fantasy terrain designed by Heatherwick Studio, the aesthetics of imbricated areas persist. Regardless of its opening final 12 months, upon arrival you’ll discover a well-recognized mixture of oxidized steel, uncovered concrete, and managed wild flora as you’re ushered by to the concession stand or the amphitheater. Additionally, you’ll be politely knowledgeable by attendants that no bikes are allowed on the island. Little Island’s flying saucer landed with a price ticket of $260 million, whereas establishing the QueensWay, it’s estimated, will price $150 million. One was the pet undertaking of an actual property mogul; the opposite will probably have to proceed to wrangle public funds to present New Yorkers a brand new place to stroll. In the meantime, small neighborhood parks throughout town domesticate a extra genuine form of decay, the results of disinvestment.

Michael Nicholas is an editor at Failed Structure.

[ad_2]

Source link