[ad_1]

Brian D. Goldstein’s The Roots of City Renaissance: Gentrification and the Battle over Harlem accounts for the transformation of the Manhattan neighborhood from the Sixties to the current. He locates the supply of this ambition with radical social actions within the Sixties that fought for management over their a part of New York. Within the following a long time, trajectories modified, and the objective remodeled to turn into a spot of financial progress, with growing wealth and retail choices. Goldstein paperwork how, on this historical past, gentrification resulted from inner grassroot efforts moderately than the inflow of actual property–thirsty outsiders.

The guide was initially revealed by Princeton College Press in 2017. In the present day, it has been launched in an expanded version. Its foreword, by historian Thomas J. Sugrue, is completely reproduced under and presents an appreciation of the historical past that Goldstein traces in his scholarship.

“Stroll by means of the streets of Harlem and see what we, this nation, have turn into.” So concluded James Baldwin’s searing 1960 account of his native Harlem, a spot with tasks “as cheerless as a jail . . . colorless, bleak, excessive, and revolting,” wanting over “invincible and indescribable squalor,” occupied and contained by white law enforcement officials. When Baldwin wrote, Harlem was hemorrhaging inhabitants. Its foremost enterprise district, one hundred and twenty fifth Avenue, nonetheless had its well-known audio system’ nook and a few venerable establishments, however a lot of its storefronts had been vacant. The encircling residential blocks had been pockmarked with uncared for and deserted buildings. Lots of Harlem’s once-grand brownstones had been chopped up into boarding homes or, after years of neglect, boarded up.

Greater than six a long time later, Harlem nonetheless has pockets of squalor, some bleak streetscapes, and a big share of the town’s mid-twentieth-century modernist public housing. However a lot of the neighborhood right this moment could be unrecognizable to Baldwin. Now one hundred and twenty fifth Avenue is residence to main chain shops, a mall, a multiplex movie show, and a high-rise workplace constructing that homes the workplaces of former president Invoice Clinton. White faces are commonplace in native cafés, huddled in entrance of their laptops, sipping single-pour coffees. It’s potential for an uptown diner to decide on between competing French bistros, a couple of movie star chef–helmed eating places, or some renovated soul meals locations, hearkening to the neighborhood’s more and more distant previous as a magnet for southern black migrants. Michael Henry Adams lamented “the top of Black Harlem” in a 2016 New York Occasions opinion piece.

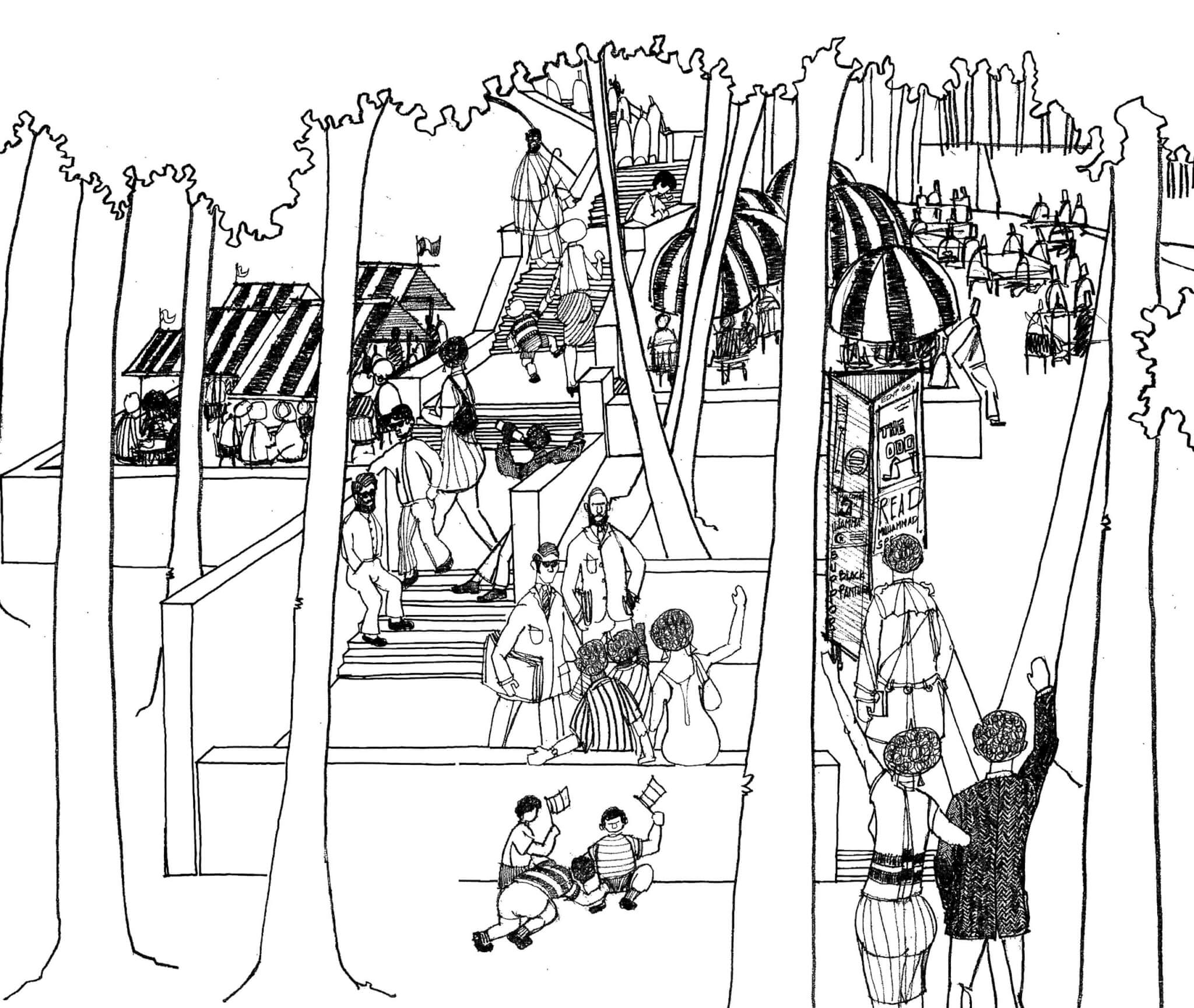

Brian Goldstein tells the story of Harlem within the second half of the 20 th century and early twenty-first by means of a wealthy account of the utopian architects, black radicals, formidable neighborhood builders, integrationists and racial separatists, squatters and self-described city pioneers, and public officers, planners, and policymakers who had been collectively chargeable for the neighborhood’s transformation. Within the pages that observe, Goldstein introduces us to visionary architect J. Max Bond Jr., who envisioned a brand new Harlem after spending time as a planner in Ghana; neighborhood activist Alice Kornegay, who fought to melt the arduous edges of the East Harlem Triangle, a bleak stretch of housing surrounded by trade and a freeway; Philip St. Georges, a frontrunner of the working-class homesteading motion who took credit score for coining the time period “sweat fairness”; and Deborah Wright, an Ivy League–educated planner who harnessed federal Empowerment Zone funds to lure deep-pocket financers and launch Harlem USA, the neighborhood’s first shopping center.

For all of his guide’s vivid element, Goldstein has written way more than an area examine. He makes use of Harlem to make clear a vital interval in American city historical past: a second of disjuncture, starting within the Sixties, when liberal city planning (particularly modernism and concrete renewal) got here beneath siege from each right- and left-wing critics. Because the “New Deal spatial order,” as Goldstein has known as it, started to fall, Harlem grew to become contested terrain concerning the way forward for race, financial improvement, and public coverage. In Harlem, probably the most influential problem to liberal planners got here from advocates of neighborhood management, who noticed a possibility to undo the injury wrought by the federal bulldozer and a long time of disinvestment by redirecting energy to the individuals. Advocates of radical democracy pushed for participatory city planning instead of top-down initiatives, insisting that architects and policymakers be accountable to the communities they served. In Harlem, Black Energy advocates framed the wrestle as one for neighborhood management. They seen Harlem as an inner colony, topic to white self-discipline and management for the extraction of black hire and labor for white revenue. However moderately than despairing on the seeming intractability of Harlem’s issues, they reimagined the neighborhood in utopian phrases, the place a previously oppressed individuals could be liberated by means of black self-determination and financial management.

Impressed by historian Robin D. G. Kelley, Goldstein describes the “freedom goals” of Harlem’s visionary planners, architects, and grassroots activists, impressed by Black Energy, African decolonial struggles and nationalism, and the burgeoning Black Arts Motion. They envisioned black prospects spending their {dollars} at black companies that employed neighborhood residents and reinvested in Harlem, moderately than siphoned outward. They checked out Harlem because it had advanced over the 20 th century and noticed not simply its squalor but in addition its magnificence and cultural wealth—to not point out its potential financial energy.

Harlem’s freedom goals, like all utopian visions, collided with on a regular basis political constraints and harsh financial realities. Harlem’s inhabitants continued its sharp decline during the Nineteen Nineties, and the neighborhood was ravaged by ongoing disinvestment, a wave of arson and property abandonment, and harsh AIDS and crack cocaine epidemics, all worsened by a collapse of public dedication to cities. The novel insurgency towards liberal planning coincided with the start of the federal authorities’s lengthy, regular withdrawal from city spending. The late Sixties and Seventies noticed a bipartisan backlash to what many perceived because the “excesses” of the Warfare on Poverty, fueled by white animus towards civil rights protests and concrete rebellions. Federal austerity insurance policies beneath Nixon and Carter left financially strapped cities, together with near-bankrupt New York, to select up the items. Native and state officers, unwilling to boost taxes, appeared for options to city issues within the personal sector: this choice left housing, neighborhood improvement, job coaching, and schooling to public-private partnerships and to small-scale nonprofits, together with Harlem’s a number of neighborhood improvement firms, many based by activists who hoped that they’d be brokers of black self-determination and neighborhood management. The perversity of devolution was that it shifted duty for generations of city woes from the state to these communities with the fewest sources. Self-determination devolved into self-help.

Harlem’s neighborhood builders didn’t surrender their efforts however tailored to the brand new period of fiscal constraint. They relied on new, largely underfunded federal packages, together with neighborhood improvement block grants, modest job coaching funding, and low-income housing tax credit. Because the state withdrew from the development and upkeep of inexpensive housing, they launched small-scale efforts to revitalize housing inventory and meet the wants of poor and working-class residents, who had been led by a various group of squatters, homesteaders, and church-based nonprofits. All of them had the desire, if not the capability, to stem a long time of city disinvestment and racialized poverty. Probably the most radical of Harlem’s neighborhood organizations withered, unable to faucet federal neighborhood improvement funds. However neighborhood improvement firms with extra skilled employees, monetary savvy, and political connections had been in a position to survive and even thrive. In consequence, Goldstein argues that ultimately “the communitarian hopes of the Sixties” gave means “to a tremendously tempered, more and more privatized imaginative and prescient of the longer term.”

By specializing in the shift from large-scale city coverage to small-scale redevelopment efforts, from neighborhood self-determination to privatization, Goldstein powerfully weighs in on questions central to the historical past of city coverage and planning. How did the rising emphasis on neighborhood improvement—on rebuilding single blocks and even single buildings—examine to the grandiose and sometimes problematic efforts of city renewers? What does “neighborhood” imply in a big, socioeconomically various, and politically fractious neighborhood like Harlem? If a simply and equitable system of improvement requires participatory democracy, who speaks for the neighborhood? Goldstein presents an unromantic account of community-based improvement, exhibiting how ministers, landowners, protestors, architects, and public companies all jostled for management over scarce sources, political legitimacy, and in the end Harlem’s future.

The destiny of Harlem has all the time been outlined by the entangled relationship of race and concrete area in trendy American city historical past. Goldstein grapples with profound questions of easy methods to reconstruct a racial order by means of a restructuring of city area. Was it potential to beat generations of racial inequality in a neighborhood and a metropolis that remained extremely segregated by each race and sophistication? Or may racial separation be a liberatory drive? What are the prices and advantages of racial and financial integration? Would new developments, supposed to “de-slum” Harlem, drive out probably the most weak residents? Who advantages and who loses from reinvestment?

All of those questions result in the guide’s most necessary contribution: its rigorous reconsideration of the method of gentrification. Is gentrification the reason for, or the answer to, city decline? Or it’s neither? Standard accounts of late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century Harlem have typically targeted on change over time moderately than continuity, and nothing is extra symbolic of change than the looks of white “pioneers,” the artistic class, and the rent-seeking financiers and builders who rushed in to benefit from low-value properties that may very well be transformed into high-value property. Observers of adjusting Harlem, starting within the Eighties, debated gentrification. For metropolis officers like Mayor Ed Koch, attracting funding and new residents to Harlem was key to revitalizing New York, stemming inhabitants decline, and producing new tax income. For students and antipoverty reformers within the late twentieth century, knowledgeable by sociologist William Julius Wilson, attracting a brand new center class in Harlem would offer position fashions for the poor and finish the isolation of the so-called city underclass. For boosters, upgraded brownstones and a rising white inhabitants had been proof that Harlem’s lengthy decline had lastly reversed. On the opposite aspect, gentrification’s critics argued that whites would displace blacks, that Harlem’s distinctive tradition could be homogenized, and that the brand new types of expropriation, together with excessive rents and rising land values, would solely profit financiers and builders.

For all of their variations, either side within the gentrification debate share the view of gentrification as a top-down course of, imposed on communities from the surface. In consequence, narratives of gentrification typically have interaction in their very own type of displacement, treating longtime neighborhood residents as both obstacles to city regeneration or as helpless victims of malevolent exterior forces. In contrast, Goldstein offers voice to the big selection of actors who remade Harlem, attentive to their positive aspects and losses, totally conscious that the best-intentioned community-based efforts had combined penalties. He reveals how the squatters who occupied vacant buildings in Harlem impressed a motion of homesteaders who marshaled metropolis sources to rehabilitate empty buildings and add modest positive aspects to the neighborhood’s inventory of inexpensive housing. And he notes the frequent floor—and variations—between working- and middle-class Harlemites who renovated long-abandoned rowhouses and, within the course of, made the neighborhood extra enticing to exterior traders, together with builders. He additionally reveals what number of neighborhood management activists jettisoned their hopes that black-owned companies would save Harlem for the modest victories of attracting supermarkets or chain shops that offered higher-quality items for extra inexpensive costs than nook markets.

Harlem right this moment solely superficially resembles James Baldwin’s childhood neighborhood. Nevertheless it stays a posh and important place the place gentrified rowhouses abut huge tracts of public housing, the place road distributors jostle for patrons’ consideration exterior upscale procuring malls. For each wine bar there are dozens of nook bodegas with cashiers shielded by bulletproof glass. Regardless of the seen enhance of white residents, it stays a majority nonwhite neighborhood. The neighborhood’s common revenue has risen, however it’s nonetheless far poorer than the close by Higher East Facet and Higher West Facet.

Within the pages that observe, Brian Goldstein reveals that there was nothing inevitable about Harlem’s transformation. In the present day’s Harlem is the results of still-incomplete struggles for justice. Its streetscapes, from the tasks to luxurious condominiums, mirror competing and unresolved visions of its future. Harlem’s homegrown planners and activists and visionaries didn’t play on a stage area; their victories had been formed and constrained by selections being made in metropolis corridor, in company headquarters and banks, and in Washington, DC. To return to James Baldwin, we will nonetheless stroll the streets of Harlem, as he did, and see what the neighborhood, the town, and the nation have turn into. And thru the eyes of the neighborhood activists, planners, and builders whose histories are instructed right here, we will think about what Harlem may need been and what it would nonetheless turn into.

Thomas J. Sugrue is Silver Professor of Social and Cultural Evaluation and Historical past and affiliated school member within the Wagner College at NYU.

[ad_2]

Source link